Archives

-

Myth, Perception and Time

Vol. 1 No. 2 (2025)There is so much to say about walis tingting (Tagalog) or silhig (Cebuano), a broomstick popular in the Philippines, Southeast Asia, India, and China. Made from the midribs of mature coconut leaves, walis tingting is an essential cleaning instrument in almost every Filipino home, central or remote. Tied together on their axils using a twine, rope, or rubber, walis tingting clears the ground and gathers fallen dried leaves of trees, including plastic waste littering the surroundings, ready to be burned. Walis tingting also sweeps away dust piling up on our home appliances and equipment, or removes all those spider webs hanging on the ceilings or attics of our homes. It is a simple instrument, but its use in the household is unprecedented.

But there is more to it than meets the eye. In the Philippines, your childhood would not have been complete without walis tingting as a disciplinary instrument of sorts. Do you remember your mother or father hitting you with it when you did not listen to them? Walis tingting would have hit and hurt your arms or legs if you had ignored your parents’ order to do the household chores before playing. So, you followed them. Walis tingting had conditioned our minds to listen to our parents; if not, we would get hurt.

Sigbin or amamayong. Oil on canvas. 48" x 36" by Edwin Tuazon (Artist)But there is more. Mythology and folklore remind us of walis tingting as the main vehicle of a popular and powerful mythical creature lurking in darkness - the aswang, kikik, manananggal, or sigbin. Folklore has it that the aswang, kikik, or manananggal uses walis tingting as its medium to be able to fly to nearby towns during full moon, ready to devour the flesh of animals and suck their blood, including newborn infants. Sigbin, on the other hand, although it walks backwards slowly, can hop or jump vertically and explosively, and utilises its powerful stealth ability to deceive its prey. Conversely, the same walis tingting is used as a disciplinary tool by our parents to keep us inside our homes when darkness comes because they knew that aswang, kikik, manananggal or sigbin is up above the clouds or underneath those elevated wooden floor, scanning every home, all set to attack and spread terror to a quiet community preparing to fall asleep. And our parents’ intuition is to lock all windows and doors after hanging garlic outside those windows and doors, and after tossing salt around the house because aswang, kikik, manananggal or sigbin cannot stand the excruciating effect of salt on their skin, and the pungent smell of garlic that makes them vomit the very blood that quenches their thirst and gives them the energy and satisfaction they need the most.

Source: Freerange Stock/iStock by Getty Images (2021)But this is all a myth, isn’t it? So, what are myths? In Malinowski's (1926) words, myths are not meant to be read as explanations, but are active parts of culture like commands, deeds, or guarantees, certifying that some sort of social arrangement is legitimate. In short, myths have some pragmatic social functions. Tradition takes a special role in this indispensable job which myth performs for culture: "Myth expresses, enhances and codifies belief; it safeguards and enforces morality; it vouches for the efficiency of ritual and contains practical rules for the guidance of men... a pragmatic charter of primitive faith and moral wisdom. Myth is thus a "hard-worked active force," covering the "whole pragmatic reaction of man towards disease and death" and expressing "his emotions, his foreboding" (as cited in Strenski, 1992). In short, myths linger in the metaphorical and the symbolic that somehow muddle the very reality of the world of man. Some communities that rely on the symbolic meanings of myths may take for granted natural, geological or meteorological explanations for disasters, thereby slowing down the adoption of modern science and promoting fatalism and inaction. Seeing disasters as divine punishment, fate, or the work of supernatural beings, people may develop the idea that nothing can be done to mitigate these disasters using human intervention, a fatalistic view that can cloud reality and action.

In the words of Roland Barthes (1957), mythology seems to harmonise with the world, not as it is, but as it wants to create. It renders itself ambiguous as it claims to understand reality yet has some complicity with it. The metalanguage of myths “acts nothing; at the most, it unveils – or does it? To whom?” (p. 156). Any myth with some degree of generality is, in fact, ambiguous because it represents the very humanity of those who, have nothing, have borrowed it. It is not only from the chaos of the public and enormous social ills that one becomes enraged, estranged or alienated, but it is sometimes also from the very object signified by the myth (Barthes, 1957). The fact that we “cannot manage to achieve more than an unstable grasp of reality doubtless, gives the measure of our present alienation: we constantly drift between the object and its demystification, powerless to render its wholeness. For if we penetrate the object, we liberate it, but we destroy it; and if we acknowledge its full weight, we respect it, but we restore it to a state which is still mystified” (p.159). It would seem that, as we continue to navigate myths in our lifeworld, “we are condemned for some time yet always to speak excessively about reality” (p.159). This is probably because ideologism and its opposite are types of behaviour which are still magical, terrorised, blinded, and fascinated by social reality and the social divide.

From a realist and pragmatic viewpoint, myths are a widely held but false belief of a fictitious or folkloric character, a misconstrued understanding, and a flawed logic, yet it seems to be alive in the consciousness of many of the Filipino people because the overarching aswang myth remains popular in family gatherings and events such as All Souls Day, All Saints Day, Halloween, or even Holy Week. The very mythical story that the Filipino people share constitutes the very existence of the myth of the aswang, kikik, manananggal, or sigbin and such a myth invigorates the very stories, such that they are deeply etched in their minds. It is a living knowledge penetrating almost every Filipino home. It is in these stories that the power of such a mythical creature pervades and continually deceives many Filipinos to believe in a supernatural being, a creation of the imagination of the Filipino spirit who had experienced all the terror and trauma from the brutal forces of colonisation, war, and torture. Deception becomes delusion that eventually clouds logic and blurs the line between fact and fiction, reality and fantasy, and abstraction and materiality. Citing Malinowski, Strenski (1992) postulates that myths are latter-day "noble lies," but ones without which common folk would be unable to cope with the final meaninglessness of human existence. Although myths are functionally or pragmatically useful in stilling human fears—mere biological palliatives— they are utterly without basis in reality. Myths act in this unconscious and in a direct way, speaking subrationally to our deepest instincts for survival, fuelled by our desire and will to believe in something we do not see.

We encourage you to read Issue 2 of Simbolismo, which features Nimrod Delante’s semiotic exploration and interpretation of descriptive accounts of and about aswang in the academic texts. He performed a critical reading of 28 articles on aswang and utilised Peircean semiotics as a lens through which aswang significations are captured in his interpretation. Seven striking themes that stand for something bigger (signs) emerged with their possible interpretations (objects). Nimrod shares thought-provoking insights about how aswang has permeated the Filipino ways of seeing and knowing, and what we can do about this seemingly disturbing phenomenon residing deeply in the Filipino consciousness on the levels of theory or abstraction, pedagogy, state of mind and behaviour, cultural practice, and choice.

Enjoy reading!

-

Lusong ug Alho

Vol. 1 No. 1 (2025)

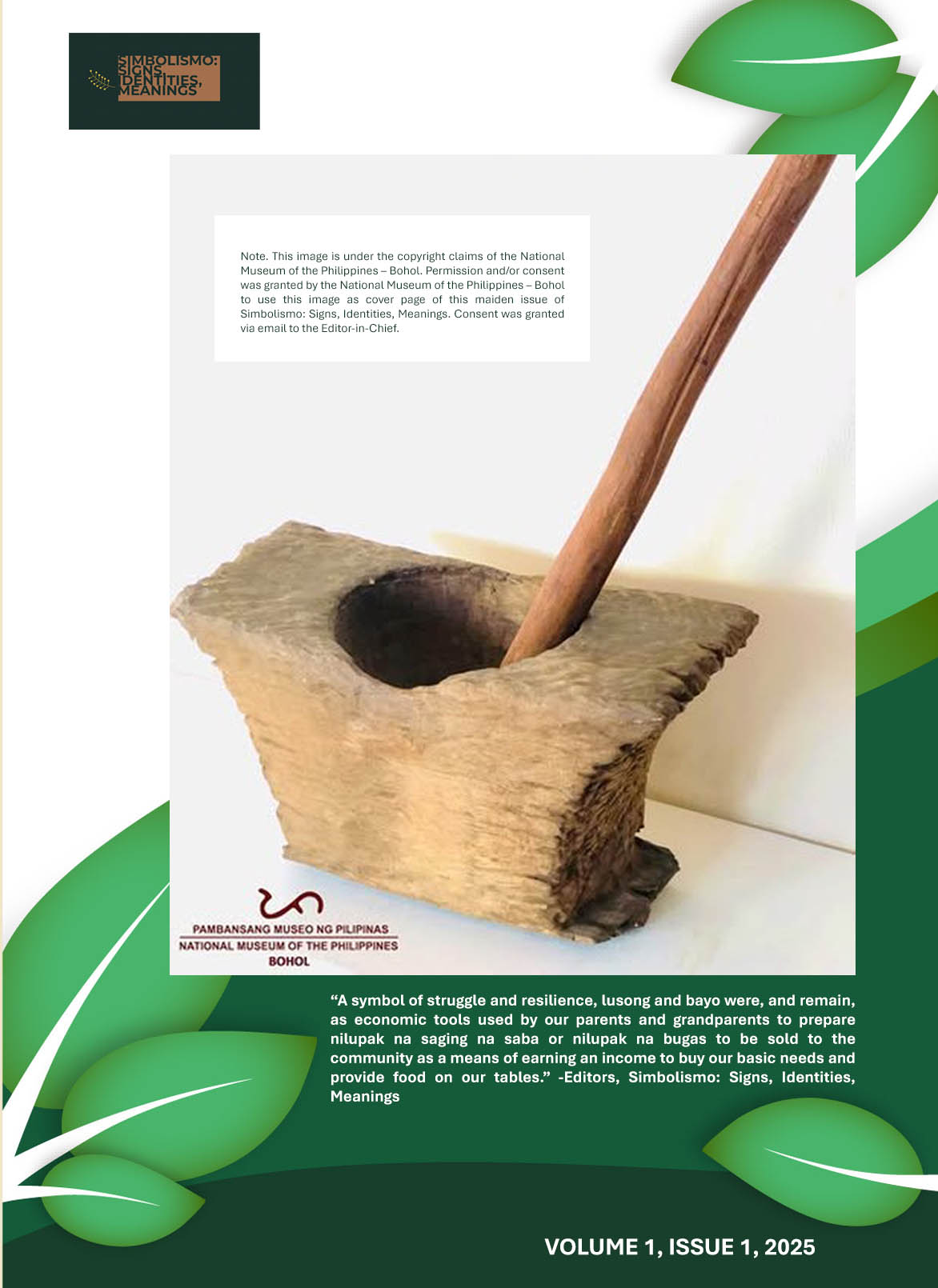

Lusong (mortar) and alho or bayo (pestle) are deeply symbolic of the struggles of Filipino life and the embodied strength of the Filipino to provide food for every Filipino home. Yes, modern technology has encroached on our ways of preparing food, but this tradition and heritage remain an integral part of life in the provinces of the Philippines. Whether you are pounding sun-dried rice pellets and cacao seeds or making nilupak na saging na saba or nilupak na bugas, lusong and bayo will always deliver. All you need is your physical prowess and the joy, presence, and excitement of family members taking turns in pounding what is in the lusong until food is ready to be served.

Lusong is carved from a huge trunk of a tree “hollowed out in the middle and shaped like an inverted trapezoid upon a wider base” (National Museum of the Philippines – Bohol, 2020). Alho or bayo is a long, thick, heavy wooden stick that is used to pound or stamp food produce inside the lusong. Bayo is carved delicately and is smooth to the human hands due to the warmth of its touch. The longer it is used, the smoother it becomes. It doesn’t grate, break, or shatter easily. In the words of Roland Barthes (1957), “wood is a familiar and a poetic substance… it wears out, but it can last a long time,” just like the bayo.

A symbol of the simplicity of life, lusong and bayo are traditional instruments that our ancestors used to process food and prepare tasty and delicious dishes for their families. Easy to make and environmentally friendly. Carved straight from old trunks of trees. Poetic and lasting. Seasoned by time.

A symbol of struggle and resilience, lusong and bayo were, and remain, as economic tools used by our parents and grandparents to prepare nilupak na saging na saba or nilupak na bugas to be sold to the community as a means of earning an income to buy our basic needs and provide food on our tables.

Note: The cover photo is an image owned by the National Museum of the Philippines – Bohol (taken from their Facebook page). The National Museum of the Philippines - Bohol granted permission and/or consent to use this image as the cover page of the maiden issue of Simbolismo. Please contact the National Museum of the Philippines – Bohol if you wish to use this image under their copyright claims.